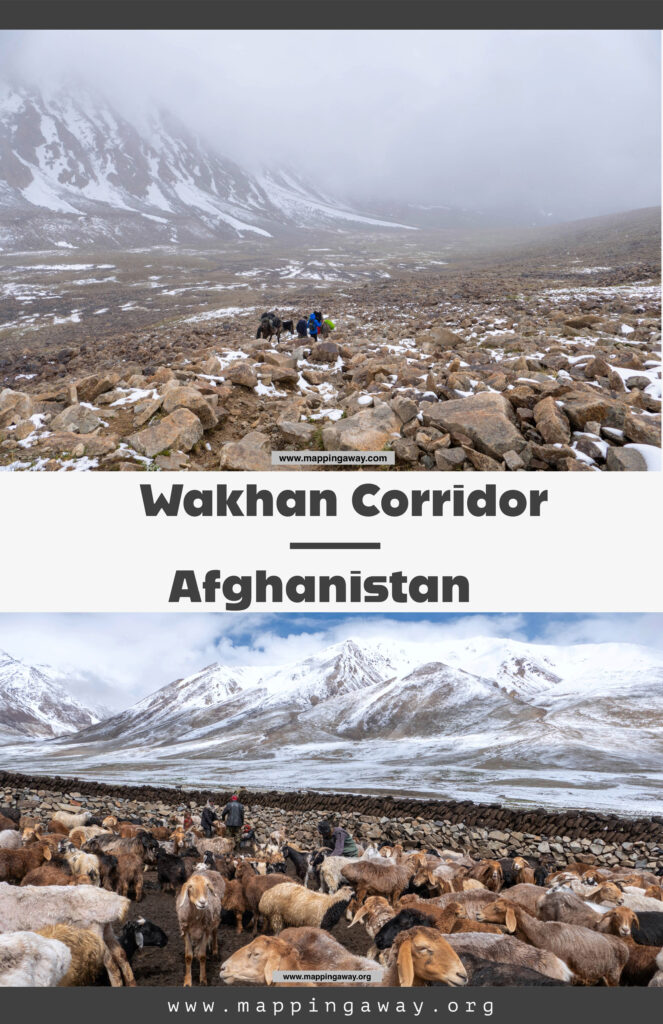

This is a 14-day itineary road trip, including a 3-day hike. This trip is enthralled by vast valleys and plateaus, goat and yak shepherds, stately mountains, high-altitude flowers, etc.

In the far east of Afghanistan, a narrow strip bounded by the Hindu Kush mountain on the Pakistan border, the Tianshan on the China border, and the Pamir mountain on the Tajikistan border, called the Wakhan Corridor. It is in the Badakhshan province of Afghanistan. Wakhan is above 2,000 meters in elevation and gradually ascends to 3,500 in the Afghan Pamir. The remoteness, rich cultures, and majestic mountains captivated every traveler. The end of concrete roads signified the beginning of isolation and hostile environments, minimal materials, and yet, the rich cultures and diverse ethnic groups living here. Wakhan Corridor receives around 250 tourists a year.

People of the Wakhan Corridor

Two major ethnic groups live in this corridor, namely the Wakhi and the Kyrgyz people, and a small number of Pamiris. These groups practice different sects of Islam. Wakhi people live in villages, some of whom are farmers and shepherds from Lower Wakhan to Sarhad-e Broghil. They spread to Tajikistan, China, and Pakistan. They are Ismāʿīli Shias, whose imam is Aga Khan IV, and the Kyrgyz people practice Sunni Islam. Aga Khan Development Network is active in the region to provide education and training programs, sustainable agriculture, and operate hospitals, etc. The people in the Corridor are subjected to decades of marginalization by the government. And yet, the community promotes the importance of learning for all. Spoke to an organization officer about training programs for girls who face adversity, they terminated the girls’ programs and are uncertain about the future.

The Kyrgyz people are a nomadic community that spread over Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, China, and Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, about 2,000 families remain in Wakhan Corridor, and migration to its neighbor countries is always part of the conversation. Slowly, through their networks, Kyrgyz migrated and settled in Kyrgyzstan and Turkey. Anthropologist, Tobia Marschall indicates two migration waves have happened in the Kyrgyz community since 1945. The first was in 1978 when the entire 1,300 Teyet oruq (tribe) Kyrgyz fled to Pakistan with the last local leader (khan) and then resettled in Turkey. The second wave happened from 2017 to 2021 with Kyrgyzstan’s sponsored repatriation program. Between 2017 and 2019, the program resettled 100 Kyrgyzs to the eastern Naryn and southern Osh provinces, according to Radio Free Europe. It was reported in 2021 that “300 Kyrgyzs fled across the border into Tajikistan with their livestock” in the wake of the Taliban capturing Badakhshan. They returned to the Afghan Pamirs when the United Nations denied their requests. Here are some scholars’ research that I found helpful to understanding the Pamir and the Afghan Kyrgyz: Ted Callahan, Tobia Marschall, and M. Nazif Mohib Shahrani.

**Quick facts on Kyrgyz’s social organization and structures. Cultural Intelligence for Military Operations: The Kyrgyz of Afghanistan

**Wakhan and the Afghan Pamir Brochure by Dr. John Mock & Dr. Kimberley O’Neil

**Pamir: Forgotten on the Roof of the World by Matthieu Paley

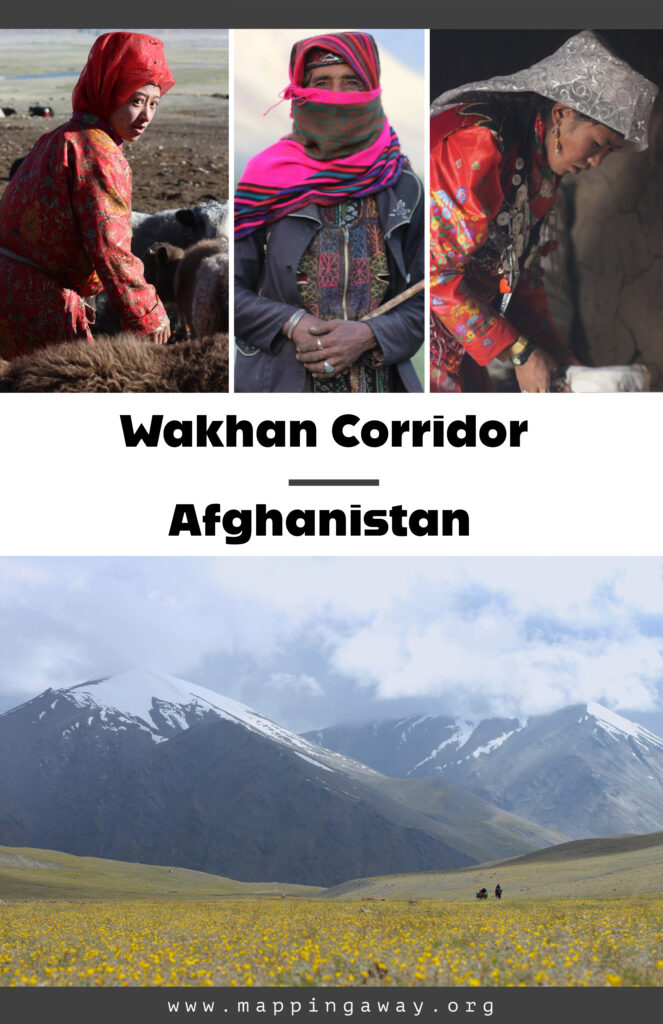

Women & Girls

Against the backdrop of women’s role in Afghan society, Wakhahi and Kyrgyz women have a well-defined role in their families, and it depends on whether they live in a town, a village, or nomadic. Traditionally, Wakhahi women work on farms and are responsible for herds, milking, making butter, yogurt, etc. In the winter time, off-season, they have time to stitch clothing. The current government is attempting to limit their mobility at home. Their traditional clothing is colorful, and a headscarf is loosely tied around their head. Preferably a red dress, it is a color against evil. Married women wear the blue chadarees seen in Eshkashem. Recently, more young girls prefer to wear black masks than the burqa decorated with glittering beads. It extends to villages. I was told that because of the current policy, women must wear a burqa and a black mask is an alternative.

In the high plateau during summer, both Wakhai and Kyrgyz women milk the herds in the morning and evening. They boil the milk and stir until it evaporates to only the fat. Yogurt rice is a popular diet. Collecting animal dung is important to keep the stove fire on. They carry a large bamboo basket, follow the animals, and return home with a full basket. Young girls walk to nearby streams or water pipes, and fetch water.

Kyrgyz women traditionally wear a two-piece red dress or a dress and tight pants under. The red dress sometimes with green natural patterns or golden patterns. They wear a red velvet vest, some with beautiful embroidery. Red is a symbol of new beginnings and the start of life, and as a protection against evil eyes. The married women wear a long white scarf over a cap to cover their hair, which is symbolic of marriage. The unmarried girls wear a long red scarf. Many shiny, metal objects, and buttons were tied on their red vest. Are they signs of wealth? Amulet? Access to materials is difficult. It is worth noting that the bride’s dowry is expensive in the Pamir. Men could wait longer to save up for marriage.

A quick note on Education/health in the Afghan Pamir

Although the Kyrgyz move a very few times a year, they scatter in a vast plateau. Near the Chaqmantin Lake, a newly built hospital by the Aga Khan. There is one doctor and a few staff. During a short conversation with the doctor, infant mortality is high in the Pamir. Locals travel to Fayzabad to see doctors, which takes a week to get there and is expensive. Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) is the most common visit to the clinic.

In the Kyrgyz village of Uech Jalgha, five male teachers are sent by the current government to the Little Pamir. Some of them were once soldiers or civil servants in the previous government, but now they are teaching the Kyrgyz students for three months in the summer, and they will go back to town in winter. It is common in many remote parts of Afghanistan that teachers are sent by the government to teach in remote villages. The same for the doctor who was stationed in the Little Pamir for several months.

Villages near Sarhad Borghil and in the Little Pamir are far, far away from access to school supplies and medicines. Children always ask for pens and adults might ask for medicine or creams (eye drops, muscle reliever, cold relief, etc). If you are generous, they always appreciate your gifts. Please think that even with money, they have to travel one to two weeks to a town to get supplies.

Best time to Visit

Wakhan Corridor opens from June to August. Shepherds’ migration to the lowlands begins in late August and the cold wind slowly moves in. Winter in the Afghan Pamir goes below 0 Celsius.

Solo or Tour?

If you are on a long tour, Wakhan Corridor and Afghan Pamir are doable for solo travelers. You need to arrange logistics, permits, food, and equipment in Eshkishim. Some travelers have done it.

Travel with A local guide?

Wakhi tour guide is for his knowledge of the area, his language skills, and his network. However, one must accept that guides are not encyclopedias and have limited knowledge of other ethnic groups or the country. Travel to Wakhan Corridor with a non-Wakhik speaker, your guide will need to hire a local guide for the journey. Although Afghan Pamir is home to the Kygyrz, the Kygyrz porter I had had limited knowledge of hiking routes. He always restricted mobility due to responsibilities, such as tending the herds.

I found Ibrahim at a Central Asian Forum and immediately WhatsApped him about the date availability and itinerary. He operates the Afghan Tour Organization with his partners. He also owns a pharmacy in Khandud, where he is from. I met his two aunts, cousins, and son. It costs $200 per day, including food, accommodation, and transportation. From Eshkashim onward, a 4-wheel drive is a must and it costs $100 a day for the driver and his car. The road becomes unpaved and rocky. Sometimes, we have to cross melted snow that has turned into a river. If the water runs too fast, it is unsafe to cross. If you decide to visit Wakhan, here is his number +93 749229030 and ibrahimhamdard030@gmail.com

Permits

The Ministry of Information and Tourism requires one to apply for permits once in an Afghan city. I stayed one night in Kunduz as I needed to get my permit stamp from the Ministry. Upon arrival in Fayzabad, the capital city of Badakhshan province, we visited the Ministry for the province permit. Subsequently, we visited the district permit office in Eshkashim. Finally, we went to the Wakhan government office after entering the Wakhan National Park in Khandud.

What to bring for permits?

10 or more passport photos. I used 4 already.

Passport copies.

Afghan Visa (From Tajikistan border)

Tajikistan – Afghanistan Border Crossings

Day 1 Kunduz

64 KM

Kunduz Hotel is in the center, where access to restaurants and bazaars is available.

I crossed the border from Tajikistan to Afghanistan. Kunduz is the nearest city to the Shir Khan Border, where there is easy access to hotels. After crossing the border, it is required to get your visa stamp in Kunduz. If you leave the immigration office at 2 PM, you will make it to Kunduz in an hour. Rush to the Ministry to get your stamp otherwise, you have to visit it tomorrow.

Fresh and smaller cherries are in season now. They are everywhere in the bazaar.

Day 2 Leaving Fayzabad: Road to Eshkashem

390 KM

9 Hours

Marco Polo Guesthouse provides basic amenities, a squad toilet, a hot shower, and home-cooked meals.

Second day on the road, I had a bad feeling that I was getting a cold. I lost my appetite against the July heat in Fayzabad of 37 Celsius. After a long time, I wore a hijab again in the hot heat. Last time, it was in Yemen. I felt sweat sliding through my forehead and my neck was like a steamer. The light fabric of the Tajik tunic/kurta kept me cool. Outside of a restaurant in Fayzabad, two women were begging. Chadaree acted as a shade, they were hidden and eating under it.

Afghan Consulate in Khorog, Tajikistan has remained closed since the Taliban took over. The Tajikistan government is slowly establishing a relationship with the Taliban on border security. And yet, the Afghan-Tajik border market takes place every Saturday. Afghans sell their products and handicraft products in the market.

After Fayzabad, the elevation progressively ascends and the air is cooler. We left the Fayzabad heat behind. The road is along the Kokcha River, and many small villages are established along the fertile soil valley. The valley is the only lush green area in the sparsely vegetated mountains. Baharak is a small town in a valley, where fields of poppies have been harvested. Some seed pods are still found in the field.

Day 3 Eshkashem to Khandud

102 KM

Morning 9 AM

Visit the Ministry of Information and Tourism for a Permit – The first thing to do in the morning! It takes about an hour. The officers love to have a photograph with you.

Eshkashem is the main town in the region where groceries, electronics, and clothing are available. We got fruits, canned beans, pasta, and noodles for camping. Also some essentials like toilet paper.

Eshkashem is a beautiful town with tranquil surroundings. Outside of the Marco Polo Guesthouse, a water stream flows from the melted snow up in the mountain, which is their irrigation for the farmlands. The farms are well-taken care of, fenced by thorn plants. Some houses have a garden in the center of the courtyard. They grow vegetables, fruits, and flowers. And sometimes a hashish plant can be found. The neighbor bends low and washes hands in the water ditch, meanwhile, the ducks clean their feathers. The owner’s hen has adopted two duckies and they are learning “to peck” at the ground.

We have to make some logistic changes here. Ahmed is our new driver now with his Toyota Land Cruiser. Ahmed was a driver for NGOs and took them around in the Wakhan Corridor. As many NGOs departed Afghanistan, now he is driving for the tourists.

Day 4 Khandud to Sarhad-e Broghil

87 KM

Khandud is a river valley. Farming is the main activity here, and a greenhouse has been introduced all year round. The villagers receive basic food like wheat, oil, rice, etc. from the World Food Programme after harvests. What they grow is not enough to sustain the family members during the winter, and if the crops do not yield as well as the previous years, the family will suffer from hunger. Families come to the WFP collection point with their donkeys and camels.

On the way to Sarhad-e Broghil

Sarhad-eBroghil is in a valley at 3,292 meters elevation, facing the wide plain of a river. Willow trees are introduced to the plain and river bank for firewood. Sarhad is a photographic lush green plain in the summer. Cattle, camels, and goats are gazing under the warm sun. Where there’s no school, children are the shepherds. In the meantime, they enjoy playing volleyball when the sun goes behind the mountain. This is a village where I could stay for days.

The last stop is to take a hot bath. From Sarhad onward, it is a nomadic land. There is a hot spring, which is also a common bathhouse for the villagers. This means that there is no hot water in the guesthouse. Upon request, the friendly gentleman in the guesthouse can fetch spring water for your bucket shower.

Day 5 Sarhad to Chaqmatin Lake

I was told that the road from Sarhad to Chaqmatin Lake had improved since 2020, although Google Maps does not show the directions. Yak caravan and villagers walk on the main road and then hike to their summer campsites. Earlier, the path along the river was the main route connected to the inner land. The constant Taliban convoys passing through make everyone aware of their presence in the Little Pamir.

In the warm July, it’s the breeding season for mosquitoes near the lake. A swarm of mosquitoes approached when I was walking around the lake. The little purple flowers bloomed along the lake’s shoreline, as you lifted your head slowly, and across the lake, where the snow-capped peaks of the majestic Hindu Kush mountain ranges. “Roof of the world” came to my mind.

Kyrgyz Camp at Uech Jalgha

Uech Jalgha is one of the main Kyrgyz settlements in the Little Pamir. It is accessible by car. In the presence of a physical mosque, Kyrgyz and Taliban soldiers pray alongside when it’s called for prayer. This also shows the Taliban’s influences on the Kyrgyzs who used to have limited interaction with the government. Due to its location, Uech Jalgha is where tourists, officials, and traders stop for accommodation and food. Expect interesting conversations but not much hospitality.

Day 6 Chaqmatin Lake to Kurchin Village

Before we left Chaqmatin, an hour’s walk took us to another Kyrgyz village settlement. This village is much smaller and the man who hosted us is in his 40s. Children are playful and never refuse photos. Racks of dry yogurts are out under the sun; there’s a sourness to them that you either like or hate.

At a short distance from Chaqmatin Lake, the Garam Chashma is where you get to take a warm spring. It has two separate small spring pools where I enjoyed myself under the shady sun. Of course, I did some quick laundry.

Kurchin Village is a simple two-family village. When we arrived, the Kyrgyz woman was cleaning the stove and stitching the tent. It seems like they came here a few days earlier. Unexpectedly, it started snowing the next early morning. The locals know it was not a great time to travel further. Neither Kyrgyz nor Wakhi men took the part-time role of a porter. Ibrahim traveled an hour away from the Kyrgyz village to find a man with a horse and donkey, who was willing to travel with us.

Day 7 Trekking from Kurchin to Aqbelis Pass at 4,600 meters

17 KM

5 Hours

4,600 meters

Almost whitewashed in the near distance, only the yaks and yurts are visible. We were debating whether we should continue with our journey to Gormda Valley. The snow is in favor of the yaks. The bright red dots held buckets between her thighs and milking the yaks. The women were working on the animal farm, separating the baby yaks from the dris. The mother camel standing against the mud-colored house, looking lonely and desperate. Her calf ran away last night and was nowhere to be found.

10 AM

The sun peeked through the cloudy weather. Our hope was so high that we started tying bags on the donkey and packing sleeping bags. The yaks soaked in the ice-cold stream when we were crossing it to begin our journey. Nassar is an additional member of the team now with his two donkeys and a horse.

Agbelis Pass is at 4,600 meters. On the foothill of Agbelis Pass, we got caught up in a hail storm, then snow, then hail. The weather just turned upside down. At this time, it was almost impossible to continue. We set up the tent and called it a tea break.

Day 8 Gormda Valley with Wakhi Family

4,300 Meters

Unforeseen snow weather in the Gormda Valley. We spent one day in a yurt belonging to a Wakhi family who bought it from a Kyrgyz. Gormda Valley is at the foothill of Uween Sar Pass (4850 meters), a water stream wound through the valley creating a grassland. It’s a perfect haven to escape snow. From the mountaintop, dotted houses, miniature animal fences, and black dots covered the human footprint area.

How did I spend a day with the Wakhi Shepard family?

We observed the family’s daily activities from milking to boiling butter and separating the animals. Unlimited salt milk tea in the mountains. We were served with yogurt rice, milk rice, and some bread.

Day 9 Uween Sar Pass

4,850 meters

8 Hours

We started observing the weather around 6 AM. I slid the yurt fabric door into an open space, and the mountain peaks were covered in white clouds. Only the stream quietly roared as it wound down the valley. We peeked out the yurt to check the weather now and then, hoping that the sun’s rays scattered through the clouds. It was only until later, at 11 AM, that the range peaks cleared up.

Quickly, we packed and tied bags to the donkeys. Everywhere in the grassland is a route; you can walk anywhere as you wish; the problem is that you don’t know where you end up. Rocks have been washed down by melted snow and then formed into a shallow stream. I removed my shoes to cross this ice-cold river. It’s shallow but I could slip by rocks covered in algae. It felt like after taking an ice water bath, it takes a few minutes to warm up.

Uween Sar Pass is the most challenging hike and I thought we would not survive in the snow. As I ascended the pass, I rode the donkey to speed up. The wind was coming in our direction as well as snow. The animals were struggling as well. At some points, we were unable to identify the route in the rocky area; it was covered in snow.

Day 10 Nauabd to Shawr

22 KM

9 Hours

The family offered their stone house in Nauabd is very simple. Rainwater dripped through the pillars. While yak dung was burning, the smoke suffocated in a one-window house. My backpack has smelled of cow dung for many months. That night, the family made the best meal, wild spring onion rice and chickpeas. Of course with yogurt. The next day, the sun warms up the valley. I felt I could continue with the journey. The men in the photo below had dinner with us in this little stone house.

The route from Nauabd to Shawr is defined and well-used by the locals. It is trekking through the mountain ranges along the river on a narrow path. We encountered Wakhi shepherds trekking to the campsites. There is no snow being seen on this route.

By the time we got to Shawr, it was nearly sunset. There are several camping sites near the river.

Day 11 Shawr to Daliz Pass to Sarhad-e Broghil

17 KM

5 – 8 Hours

No longer has to walk on the narrow path along the river, the newly created “highway” is wide enough for a minivan to go through. We started around 8 AM and had breakfast. We arrived at Sarhad at about noon.

Day 12 Sarhad to Qeli-Panja

5 Hours Drive

Overnight at Qeli-Panja

We were relieved and celebrated when we got to Sarhad. Ahmed, our driver, was waiting in Sarhad. There is a dangerous river that we must cross before 3 PM. The first thing I’d like to do was a hot bath in Qeli-Panja. Qeli Panja is a farming valley.

Day 13 Qeli Panja to Eshkashem

Qeli Panja is a small valley village by the river. I love the quiet valley.

When we stopped in Khandud for lunch, the Wakhan National Park officers found us. They charged us $10 for the entrance fee, it was a new policy when we were in the Little Pamir.

Day 14 Eshkashem to Kunduz

I felt a bit sad leaving the Wakhan Corridor. I could not imagine the heat in the lower land of Afghanistan. In Eshkashem, only the market is where you find restaurants and street food. I spoiled myself with some aushak /dumplings. After Kunduz, I traveled to Mazar-i-Sharif as a solo traveler.

Mazar-i-Sharif: City Tour

Essential Packing

Do I need a water filter? Safe drinking water?

It depends on your hiking style. I brought a Liftstraw filter and a titanium cup. I only used the filter a few times. Families boil water from the water stream and I fill up a bottle when it cools down. I drank water from waterfalls, springs, and a fast-running river without a filter. I did not have a stomach problem.

- Towel

- Jacket

- Sun Protection: hat, sunscreen, etc.

- Electrolyte tablets for hiking

- Light sleeping bag or liner- all the accommodations provided blankets and mattresses, if you are allergic to dust mites like me, a liner should be carried.

- Hiking sticks – I found it use.ful

- Hiking shoes & compression socks

- One thermal shirt/pant

- Extra memory cards/power banks- Sarhad is the last village where you can charge your phone and camera.

- Biodegradable wipes

- Headlight

- snacks/coffee/tea /candies

Food

Food is very basic in the Wakhan. Until Sarhad, restaurants, and accommodations serve bread, eggs, yogurts, french fries, rice, and maybe fish. However, after Sarhad, stays at the Kyrgyz and Wakhis villages, and they serve meat if they have, and yogurt, cream, milk, with white rice, but no vegetables. I did not get diarrhea from eating dairy products. We bought pasta and noodles but did not get to finish all the food. I would say having a pressure cooker makes a difference if rice is your main diet. We did not have a pressure cooker, and I was unclear about who should be cooking and what we were eating when we were not near any villages.

Pingback: Guide to Floras in Wakhan Corridor, Afghanistan | Mapping Away